Sunday, June 26, 2005

رقعة الشطرنج

على رقعة الشطرنج

اشتد الحصار

جبين الملك

يتفصَّد عَرَقاً

تساءلت جميع القلاع والخيول والأفيال

والبيادق

البيضاء والسوداء

هل سينهار؟

الكل يغني الآن

لبهلوان اللعبة

تُرى

هل سيصحب

جنازة الملك

زلزال أو إعصار؟

علاء الدين

Saturday, June 18, 2005

Al-Tanboura Group of Port Said

The Ecstasy of the Sufis or the Jollity of the Bamboutis?

(previously published in Community Times Magazine, Issue No. 92, Sept. 2003)

Port Said is an originally "hybrid" Egyptian town. This only seems true when we know that such town was quite unknown until the official opening of Suez Canal in 1869. The people of Port Said may be described, and rightly so, as an amalgamation of Egypt's different "folks" especially those descending from Damietta, northern Daqahliyya and Upper Egypt. Naturally, Port Said's hybrid demographic makeup is reflected in the traditional and folkloric arts and music.

Back to Egypt's wars in 1956 and 1967, it seems that Port Said, Ismailia and Suez were the most damaged. The people of the so-called "Canal towns" had to immigrate twice. Again, Port Said's indigenous music and folk art forms had to accommodate themselves in the exile to survive. In such an atmosphere of displacement and exile a Port Said troupe for traditional music was born first in the mind of Zakaria Ibrahim, the director of the troupe now. Zakaria Ibrahim was one of those Port Saidis who had to immigrate from their hometown after 1967, sang the time-honored lyrics of both ed-dhamma and simsimiyya, and danced the bambouti dance. Paradoxically, Port Said's folk music could survive in the exile, yet it was jeopardized by a greater threat, that is, the rise of the individualistic and materialistic tendencies, which were about to render the entire tradition of Port Said's music obsolete; favoring the money-grubber, wedding-restricted "new" simsimiyya tradition.

In such discouraging situation, Zakaria Ibrahim and his deceased brother Mahmoud thrived hard to save the simsimiyya music from mutilation and extinction. The first step was to work hard so as to collect the principal musical heritage of Port Said, naturally influenced by two main offshoots: the Sufi-oriented dhamma, and the Suez-originated simsimiyya. According to Zakaria Ibrahim, "the dhamma is an immutable traditional indigenous art form, while the simsimiyya is an art form which is prone to change and experimentation". "There are two types of simsimiyya lyrics, one which author and composer is known, while the other type is pertaining to those lyrics which author/composer is anonymous", he added.

Further, the simsimiyya songs and lyrics were released out of the makhanas (a local word in Port Said's dialect referring to hashish-taking places) and experienced a drastic metamorphosis during the national rise period (1956-1973). During such period, simsimiyya songs, known among fishermen all through the Suez Canal area, expressed the national sense set aflame inside the hearts and minds of Port Said's people while resisting the English, French and Israeli conquerors during the Suez War in 1956, and then the Israeli occupation of Sinai during the war of attrition (1968-1972). Zakaria Ibrahim did not lose track of such tradition of the Egyptian national song of the simsimiyya in his sworn mission of musical tradition collection. For example, "In Patriotic Port Said" is one of the most famous songs pertaining to the Suez War.

It took Zakaria and his brother Mahmoud 9 years to collect what they had to collect of the folk music and songs of the Suez Canal region. The task was not an easy one for many reasons. Some musical troupes and ensembles, such as Al-Sohbagiyya of Ismailia, almost disappeared or were marginalized due to what Ibrahim called "the increasing privatization of Egyptian folk music". When (folk) music is "privatized", the outstanding flavor of such music dies away in favor of a more profit-oriented, individual model. Add to this that traditional music grows to be at best a fossilized art form in the national art museum, or at worst "a mouthpiece for the government", to quote Zakaria Ibrahim.

With a conviction not to let their traditional, so-called "fossilized" music conk out, the original group, which was named the Port Said Group for Popular Culture, used to arrange their free-of-charge performances on street corners and second-rate cafes only for self-assertion and self-promotion. The original troupe, which was known afterwards as Al-Tanboura Ensemble, had to depend upon craftsmen such as carpenters, fishermen, and plumbers who had to earn their living from their original careers when there are no drums to beat or strings to pluck at night.

In such circumstances Al-Tanboura ensemble was borne in early 1989, with a predetermined objective of bringing back to life the almost dead folk and indigenous popular songs performed in the past by the Port Saidis and other Egyptians descending from the Suez Canal area. Later in 1994, Al-Tanboura Ensemble participated in the Canal Cities Festival. After their smash hit in the afore-mentioned festival, Zakaria Ibrahim changed the name of the group as Al-Tanboura Group for Traditional Port Said music. Since then, the whole ensemble, orchestrated by Ibrahim, struggled their way for self-recognition and self-amusement alike. The ensemble has been invited to perform in several places in Egypt and abroad.

Al-Tanboura Ensemble was thus named after the five-or-six stringed instrument originally known to zar ritual organizers. According to Zakaria Ibrahim, "as a musical instrument, the tanboura was totally unheard of. It is an originally Sudanese stringed instrument used in the zar rituals of medicating people of unidentified illnesses through songs and music". "The tanboura is a generally pentatonic instrument, but when adapted to the local Port Said music, it was transformed, at least for us, into an Arab instrument", said Ibrahim. Due to some modifications in the number of strings and the pegs of the tanboura, it is now permissible to play such maqams as the bayyati and Rasd, the basis of popular and Sohbagiyya repertoire. Indeed, making use of such quite notorious instrument by placing it before public gaze has revolutionized the now stale, hackneyed, as it were, Egyptian folk music.

What is distinctive about Al-Tanboura Ensemble is its "multi-ethnic" character. Perhaps this "multi-ethnicity" of Port Said folk music is the most important reason why Al-Tanboura Ensemble of Port Said had, and still has, many "fans" or murids (to use Sufism's terminology). For example, the tradition of dhamma is closely associated with the zikr ceremonies originally brought over from Damietta appears to fuse with the outstanding music of Upper Egypt, especially in the import of the mizmar (folk oboe), and the simsimiyya traditions of the Canal region and took a stupendous character of its own.

Al-Tanboura Ensemble starts their monthly performance, now held at the Townhouse in downtown, Cairo by adjusting their instruments while the audience arrives. The really astonishing thing about Al-Tanboura performances is that there is only a slim line between audience and performers. In other words, it is a "democratized" performance, where there is an abundant chance for the readily exhilarated audience to come up the dance floor and dance with the performers the bambouti dance! (An originally English word "bumboat", bambouti is originally the name given to the person involved in the mid-of-the-sea business. The bamboutis are known for their pluckiness, smartness and wickedness). Originally a fisherman, a bambouti dances friskily and jollily.

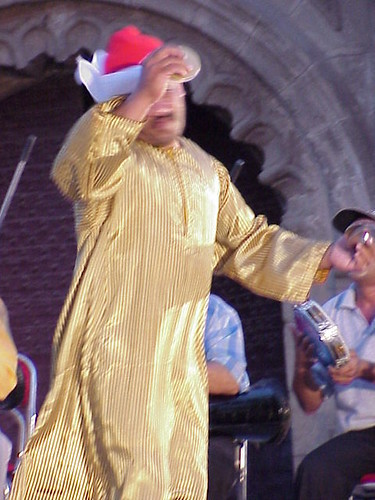

The show always starts with an improvised taqseem using the tanboura, the simsimiyya, the mizmar or the local drum. After the breathtaking taqseem, the singing, dancing, acting, mime start too. Al-Tanboura Ensemble, a blend of all ages which ranges from 70 to 30 years old, shows another source of gaiety, that is, the shocking diversity of their headwear and clothes. As if to better to defend the liberal spirit of the group, the performers wear everyday clothes and headwear which can be blue jeans and casual caps or gallabiyyas and turbans. The troupe is exclusively all-male, as by tradition, women have never been integrated into these joyous demonstrations that used to take place in cafes or streets.

During the recital, the performers find themselves calling out to each other, encouraging each other or sometimes exchanging instruments, especially the framed drum or riqq. Thrown about in a good-natured manner, the drum flies over the stage only to fall back adroitly and in time, in the hands of another performer who deftly grasps and plays it until he get dead beat, whereupon the drum is passed, in turn, to the person beside him. There are few instruments: two lyres accompanied by percussions (the tabla, single-membraned clay drum shaped like a chalice, the riqq, framed drum with little cymbals, the European triangle and the sagat or little cymbals) as well as a daring addition, the European non-membraned tambourine with jingles, and doted with small cymbals in order to second its Egyptian counterpart, the riqq. The lyre players (whether simsimiyya or tanboura), take turns to rest for a few minutes during the concert.

Whether seated or standing, Al-Tanboura performers hop up and down, wiggle about impromptu, which reflexes the dormant spontaneity, simplicity and joie de vivre acted on stage. Manifest in their headwear, taqseems, and songs, the impromptu spirit is also "out" in their folk choreography. The performers, along with some of the easily excited audience members, make for the limited space on stage to dance belly dancing, swayed-hip dancing, or the gyration of the neck borrowed from the zikr rituals which irresistibly leads to a semi-hypnotic ecstasy, but all under the denomination of the bamboutis!

Furthermore, there is no leading singer or performer amongst the 24 performers of the ensemble but all members take turns in performing as soloists, careful not to be carried away by stardom since it is the group, as a whole, that takes precedence and remains sovereign.

Everything in the show calls for optimism and joy of life. The all-smiling faces of the performers whose songs "come straight from the heart", to quote Sheikh Ragab, a 58-year old of Nubian origin. Even the circular setting, which recalls the etymological root of the dhamma rituals, summons the cozy memory of an Arabian after-supper gathering. Admittedly, Al-Tanboura Ensemble managed to revive the sohbagiyya musical style, not only that which was known in Ismailia, but also in this sense which designates any disorganized, or rather improvisational, manner of playing music.

Titled as "La Simsimiyya de Port Said", the first CD of Al-Tanboura Ensemble, made by the Institut Du Monde Arabe represents such "diversified" heritage of folk Egyptian music. Only four songs of the whole CD's songs (12 songs) are simsimiyya ones. All the simsimiyya songs follow the rasd or rast mode, regarded as the main maqam in Arabic or Oriental classical music. Examples of those songs are "Shuftu al-qamar ala l-sadr al-gamil" (I have seen the moon on the beauty's breast) and "Kawani al-hubb" (I am consumed by love). There is only one song that is both a simsimiyya and a mawwal (ballad), also played according to the rast mode. The rest of the CD ranges between dhamma and jawab dhamma songs. With no exception, the dhamma songs follow the bayyati mode. Examples of the dhamma songs are "Ya qalb salli ala al-Mustafa" (Oh my heart, pray for the Prophet), "Wa al-salat al-nabi" (Pray for the Prophet), and "Ya bulbul al-farah" (Oh nightingale of joy). The only interlude in this CD is a comic piece title "Azzil min bayti ya Saidi" (Leave my house, you Upper Egyptian).

The second product of the ensemble is a cassette tape titled "Nouh El-Hammam" (The Pigeon's Grieved Cooing) in 2002. This cassette is a continuum of the ensemble's earlier musical production in the CD. However, Zakaria Ibrahim is quite keen to introduce some innovations whether to the modes or the lyrics themselves. Now reaching a 20-hour record of folk music and singing, Al-Tanboura Group sang and sings new songs which address the current (political) situation, but within the traditional musical mode or pattern. "Ya Sohyun" (Oh Zion) and "Lotfi El-Barbari" are overtly political songs that counter the Israeli occupation of Palestine and the Anglo-American occupation of Iraq respectively. Another daring and recent innovation of the Group is the "invention" of two quite large tanbouras which correspond with the western bass and cello. The two "bass" and "cello" tanbouras, as it were, performed for the first time in Mahka Al-Qalaa Annual Festival.

Al-Tanboura Ensemble has won many prizes and awards worldwide. It has won in Jarash Festival in Jordan, and in similar festivals in Paris. They have also won the first award in the International Folkloric Music Festival in Canada in 2000. The ensemble is planning to produce another CD and a video clip titled "Ahwa qamar" (I love a pretty), a fairly unprecedented idea for a folk music ensemble.

Mr. Gamal Al-Gheitani, the renowned Egyptian novelist and editor-of-chief of Akhbar El-Adab, said once when he met, for the first time, with the emerging Tanboura ensemble in Paris: "Al-Tanboura ensemble is the musical troupe known worldwide before it is ever known in Cairo!" The question to be asked is the following: will this paradox last forever?

Thursday, June 16, 2005

From "A Lover's Complaint" by William Shakespeare

O father, what a hell of witchcraft lies

In the small orb of one particular tear!

Take Off Your Shoes and Kneel to Him

And kneel to Him

Who dwells within your heart.

There's room for none but Him,

None but Him vast enough to fill

That lonely hall.

Tuesday, June 14, 2005

تعلم اللغة بين الترغيب والترهيب

حارت الأم المستجدة في أمر ابنها ذي العام الواحد والذي كان دائم الصراخ بسبب وبدون سبب. حاولت الأم أن تحل هذه المشكلة لكن دون جدوى إلى أن هدتها إحدى الجارات العجائز إلى محاولة تعليم "اللغة" لهذا الطفل. فهل تعلم اللغة له من الأهمية بمكان تصل لتلك الدرجة الجوهرية؟

لقد أثبت علماء اللغة (وإن لم يجمعوا) على أن اللغة اختراع بشري، وهو ما كان فقهاء اللغة يطلقون عليه قديماً مبحث "الاصطلاح والتوقيف". وإذا كانت اللغة اختراعا، فإن الحاجة هي أم الاختراع، أي أن الإنسان لن يتعلم اللغة إلا إذا دعته الحاجة إلى ذلك، فذلك الطفل المزعج تعلم اللغة حتى يمكنه أن "يتواصل" مع أمه ومن ثمَّ مع البيئة المحيطة. وغالباً ما تكون الكلمات الأولى للطفل بعد مرحلة "بابا وماما" – أن لم تتزامن معها – كلمات دالة على الحاجات الأساسية للإنسان مثل الطعام والشراب وقضاء الحاجة، الخ.

وقد يتوهم البعض أن تعلم اللغة من السهولة واليسر بشكل يجعل متعلم اللغة لا يحتاج لتعلم اللغة والدربة على نطق أصواتها والإلمام بنحوها وصرفها والغوص في معانيها ودلالاتها وإيحاءات كلماتها وجملها واكتناه خباياها وإتقان أساليبها وتعبيراتها – لا يحتاج في كل هذا إلى عصا سحرية تمكنه من كل هذا وذاك بين غمضة عين وانتباهتها!

وكما هو معروف لدى القدماء من فقهاء اللغة العرب ولدى أصحاب النظرية الأدبية في الغرب سواء لدى الشكليين الروس وحلقة براغ أو لدى البنويين ومن بعدهم إلى التفكيكيين أن اللغة ذات شأن خطير، وإن كان تعلمها يبدو سهلاً ميسراً بالنسبة للطفل (تعلم اللغة الأم)، فإن هذا القدر من السهولة يعد مثاراً للحسد أو الغبطة على أقل تقدير بالنسبة لتعلم اللغة الثانية.

وقد جرت العادة منذ بدأ الاهتمام بتعلم اللغة على أسلوبين للحصول على النتيجة المرجوة هما أسلوب الترغيب أو ما يسمى في علم النفس بالثواب، والترهيب (وليس الإرهاب) أو ما يطلق عليه العقاب.

أما الترغيب فهو استمالة الطفل نحو تعلم اللغة أو بمعنى أوضح "اللغة" نفسها حيث يتعلم الطفل أو البالغ اللغة الأجنبية من حيث لا يدري ولا يعلم وذلك "بتعريضه" للغة عن طريق سماع تسجيلات بتلك اللغة (تسجيلات تُمارَس فيها اللغة بشكل طبيعي وليست تسجيلات تعليمية) أو مشاهدة أفلام أجنبية بتلك اللغة المراد تعلمها، بذلك يتعلم الطفل أو البالغ اللغة دون أن يدري أنه في حلقة درس. لكن رغم ما في هذه الوسيلة من عوامل نجاح، فإن أثرها يمتد لمهارتين فقط من مهارات اللغة وهما السماع والنطق (وإن كانت الأخيرة لا تصقل إلا بالمران المتواصل والتواصل الاجتماعي بتلك اللغة).

ويأتي مشايعو الحل الآخر وهو الترهيب أي فرض عقوبات على متعلم اللغة (وهو بالطبع الطفل في هذه الحالة!) مثل منعه من مشاهدة الحلقات المفضلة لديه في التلفزيون أو حرمانه من النزهة إذا لم يقم بحفظ كذا وكذا من قوائم المفردات وقام بحل كذا وكذا تمريناً من تمارين الصرف والنحو. إلا أن هذا الأسلوب وإن آتى ثماره لدى القليل من الأطفال الطيعين، فإنه لن يؤتي أكله مع الكثير من الأشقياء ممن هم في سني الطفولة، هذا بالإضافة إلى صعوبة – إن لم يكن استحالة – تعلم المهارتين السابق الإشارة إليهما وهما السماع والنطق واقتصار تعلم اللغة – كما يحدث وبكل أسف في مدارسنا وجامعاتنا – على مهارتي القراءة والكتابة كأن غاية طموح متعلم اللغة أن يحصل على لقب "باش كاتب" بلغة أجنبية!

إن متعلم اللغة غالباً ما يقع كما يقول التعبير الإنجليزي بين "سكيلا وكاربيديس" (وهما وحشان في الأساطير الإغريقية) أو كما يقول الشعبيون بين "حانا" و"مانا" أو كما يقول المتخصصون في اللغة بين أسلوب الترغيب وأسلوب الترهيب. والرأي أن كلا الأسلوبين – الثواب والعقاب – ضروري لتحقيق النتيجة المرجوة، فتعلم اللغة دون اتقان مهاراتها الأربع (السماع – النطق – القراءة – الكتابة) أمر لا طائل من تحته. فمتى نرى مدرسين اللغة واعين بهذا الأمر ولا نجد انقساماً كانقسام الأحزاب بين رافعي شعار "لا صوت يعلو فوق صوت الكاسيت" وأصحاب شعار "العصا لمن عصا"؟!

Friday, June 10, 2005

To Whom It May "Concern"

1. Alone, laid I among debris of dreams

among wrecked

old boxes.

My nose is filled with the smell of pain

and the masts of emptiness.

2. Alone, came I over miles of ice

sagged under my memories

dragging my worn out feet.

3. I swam, with you, amidst the surges of space

and the ravages of time

they knocked me out

I bleed.

My blood adores you

and the tiny raindrops

dandling the baby

I see in your eyes

and in your heart’s

glassy window.

4. I sat, without you, upon the roadway of grief

moved by the twilight of your eyes

and the flashes of the dark city’s

cars

wrapped by the warmth of your voice

it infatuated me.

Am I doomed to be tied

to

this lonely bed?

5. How often you come ashore to my heart,

to my ships…

how often you overwhelm the armless guard

how often I tell tales of my love

to my cities…

how often you rejoice – and I too

- my better half –

with love

that made me

… the best!

Tuesday, June 07, 2005

إلى من "يهمه" الأمر

قابعاً – وحدي – بين انكسارات الحُلُم

بين الصناديق

المحطمة القديمة

تملأ الأنف رائحة الألم

وقلوع الخلاء.

عائداً – وحدي – فوق أميال الجليد

أجرجر حِمْلاً من ذكريات

وساقي المتعبة.

سابحاً – معك – وسط أمواج الفضاء

وضربات القدر

تشج الرأس شجاً

ينفر الدم

الذي يعشقك

وصوت حبات المطر

يهدهد طفلاً

أراه في عينيك

ونافذة قلبك

الزجاجية.

جالساً – دونك – فوق رصيف الحزن

يهزني بريق عينيك

نور كشافات سيارات المدينة

المظلمة.

يلفني دفء صوتك

يأسرني

هل قدري أن أُشَدَّ

إلى

هذا السرير الوحيد؟

كم تأتين إلى شاطئ قلبي

إلى سفني

كم تهزمين الحارس الأعزل

كم أقص حكايا حبي

على مدني

وكم تفرحين ... وأفرح

- يا نصفي الأجمل –

بحبٍ

جعلني

... الأفضل!

علاء الدين

Wednesday, June 01, 2005

طاغور كما عرفته

كان طاغور فنانا بالمعنى الشامل للكلمة. فقد كتب الشعر والقصة والمسرح بل قيل إنه نمى لديه ميل نحو الرسم في سن الخامسة والستين قبل ان توافيه المنية عن عمر يناهز الرابعة والثمانين! كان طاغور – أو ظني كذلك – أن مزاجه كان ارستقراطيا لذا لم يكن "وطنيا" بما يكفي في عين الهنود ولم تؤهله مواقفه المعادية للاستعمار من نيل الحظوة عند الإنجليز!

تميز طاغور باستقالالية الرأي كما كان شاعرا رقيق المشاعر حتى إن القصة التي قرأتها له وعرفتني على عالمه كانت تقطر شاعرية.

وهذا نموذج مترجم من أشعار هذا الشاعر الهندي الذي لا ينسى...

حب لا ينتهي ... طاغور

"Unending Love"

I seem to have loved you in numberless forms, numberless times,

In life after life, in age after age forever.

My spell-bound heart has made and re-made the necklace of songs

That you take as a gift, wear round your neck in your many forms

In life after life, in age after age forever.

Whenever I hear old chronicles of love, its age-old pain,

Its ancient tale of being apart or together,

As I stare on and on into the past, in the end you emerge

Clad in the light of a pole-star piercing the darkness of time:

You become an image of what is remembered forever.

You and I have floated here on the stream that brings from the fount

At the heart of time love of one for another.

We have played alongside millions of lovers, shared in the same

Shy sweetness of meeting, the same distressful tears of farewell-

Old love, but in shapes that renew and renew forever.

Today it is heaped at your feet, it has found its end in you,

The love of all man's days both past and forever:

Universal joy, universal sorrow, universal life,

The memories of all loves merging with this one love of ours-

And the songs of every poet past and forever.